Wednesday, May 24, 2023

Behind the headline figures

It seems rather bizarre to be celebrating inflation at 8.7%, but at least it is no longer in double figures. The New Statesman however, sounds a cautionary note. The headline figure is misleading and offers no relief whatsoever to most families.

The magazine says that prices across the economy are still rising far more quickly than wages, and they are not doing so in the even manner suggested by the headline CPI rate:

The annual rate of inflation on food is still 19.1 per cent, down just 0.1 per cent from last month. In some shops – such as Lidl, where the same goods cost 24.9 per cent more than they did last year – prices are growing more than four times as fast as wages (which are up 5.8 per cent in a year).

To be absolutely clear, falling inflation does not mean prices are falling, but that they are rising slightly less quickly. For goods and services to become more affordable, inflation would have to fall below wage growth for a sustained period. This is unlikely to happen because unemployment is rising, and falling headline inflation could give employers more of an excuse to reduce or reject workers’ pay rises. At 8.7 per cent, inflation is still more than four times the Bank of England’s target. Workers across the economy are still becoming poorer at a very concerning rate.

Rishi Sunak promised at the start of the year to “halve inflation” and the latest headline inflation figure takes him some way towards that target. However, the main reason it’s lower is mathematical: CPI is a measure of how much prices have grown in the last year, and the biggest single element in recent price rises – the 54 per cent hike in everyone’s energy bill that occurred when Ofgem raised the price cap in April 2022 – is now more than a year in the past. The Prime Minister’s contribution to the fall in inflation has been to experience time passing, and then take credit for it.

This underscores just how mediocre the promise to halve inflation was in the first place: it was an offer of an economy in which the purchasing power of your income dwindles rapidly, but your impoverishment is slightly less aggressive than it was under the previous administration.

The headline figure also conceals a more disturbing trend. The prices of some goods and services, such as energy and food, can rise and fall rapidly, distorting the headline number, so “core” inflation – price rises in the less volatile parts of the index – is seen as a more stable representation of the overall temperature of the economy. Core inflation has not peaked: it rose from 6.2 per cent to 6.8 per cent in April, the highest level since March 1992.

A stubborn rate of core inflation may mean that the Bank of England is forced to raise interest rates still further, putting more pressure on low-income families who increasingly use debt to buy essentials, and homeowners who are remortgaging at much higher rates. Financial markets expect rates to peak at 4.75 per cent, which would mean they are likely to rise once more this year.

At the same time, the freezing of tax thresholds means that many middle earners such as nurses and teachers are being pushed into higher tax brackets. This squeezes their income wiping out reliefs such as child benefit and leaving precious little extra to compete with the racing prices in supermarkets.

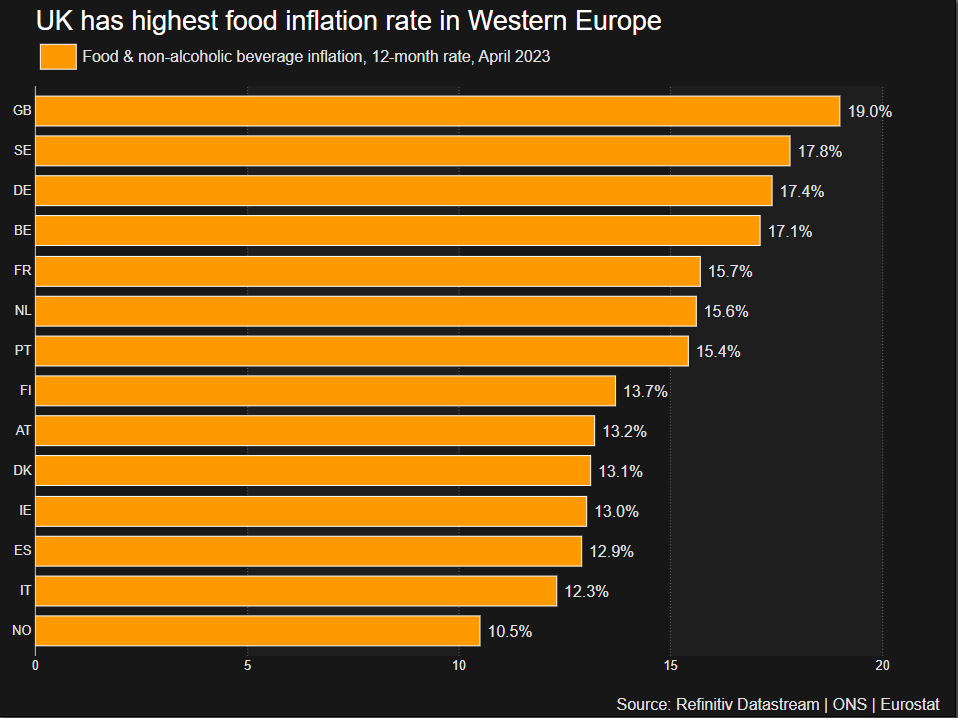

Andy Bruce of Reuters believes that the UK has the highest rate of food inflation in Western Europe, as illustrated by this graph:

He has also set out some inflation figures April 2022 to April 2023 for some key items:

Sugar +47%

Olive oil +46%

Car insurance: +41%

Eggs +37%

Natural gas +37%

Sauce/condiments +34%

Milk +34%

Small electrical hh appliances: +32%

Frozen veg +31%

Cheese +31%

Sausages +28%

Pasta +28%

Pork +27%

Non-fiction books +27%

Potatoes +25%

It is pretty scary stuff, and shows that we are a long way from escaping this cost of living crisis.

The magazine says that prices across the economy are still rising far more quickly than wages, and they are not doing so in the even manner suggested by the headline CPI rate:

The annual rate of inflation on food is still 19.1 per cent, down just 0.1 per cent from last month. In some shops – such as Lidl, where the same goods cost 24.9 per cent more than they did last year – prices are growing more than four times as fast as wages (which are up 5.8 per cent in a year).

To be absolutely clear, falling inflation does not mean prices are falling, but that they are rising slightly less quickly. For goods and services to become more affordable, inflation would have to fall below wage growth for a sustained period. This is unlikely to happen because unemployment is rising, and falling headline inflation could give employers more of an excuse to reduce or reject workers’ pay rises. At 8.7 per cent, inflation is still more than four times the Bank of England’s target. Workers across the economy are still becoming poorer at a very concerning rate.

Rishi Sunak promised at the start of the year to “halve inflation” and the latest headline inflation figure takes him some way towards that target. However, the main reason it’s lower is mathematical: CPI is a measure of how much prices have grown in the last year, and the biggest single element in recent price rises – the 54 per cent hike in everyone’s energy bill that occurred when Ofgem raised the price cap in April 2022 – is now more than a year in the past. The Prime Minister’s contribution to the fall in inflation has been to experience time passing, and then take credit for it.

This underscores just how mediocre the promise to halve inflation was in the first place: it was an offer of an economy in which the purchasing power of your income dwindles rapidly, but your impoverishment is slightly less aggressive than it was under the previous administration.

The headline figure also conceals a more disturbing trend. The prices of some goods and services, such as energy and food, can rise and fall rapidly, distorting the headline number, so “core” inflation – price rises in the less volatile parts of the index – is seen as a more stable representation of the overall temperature of the economy. Core inflation has not peaked: it rose from 6.2 per cent to 6.8 per cent in April, the highest level since March 1992.

A stubborn rate of core inflation may mean that the Bank of England is forced to raise interest rates still further, putting more pressure on low-income families who increasingly use debt to buy essentials, and homeowners who are remortgaging at much higher rates. Financial markets expect rates to peak at 4.75 per cent, which would mean they are likely to rise once more this year.

At the same time, the freezing of tax thresholds means that many middle earners such as nurses and teachers are being pushed into higher tax brackets. This squeezes their income wiping out reliefs such as child benefit and leaving precious little extra to compete with the racing prices in supermarkets.

Andy Bruce of Reuters believes that the UK has the highest rate of food inflation in Western Europe, as illustrated by this graph:

He has also set out some inflation figures April 2022 to April 2023 for some key items:

Sugar +47%

Olive oil +46%

Car insurance: +41%

Eggs +37%

Natural gas +37%

Sauce/condiments +34%

Milk +34%

Small electrical hh appliances: +32%

Frozen veg +31%

Cheese +31%

Sausages +28%

Pasta +28%

Pork +27%

Non-fiction books +27%

Potatoes +25%

It is pretty scary stuff, and shows that we are a long way from escaping this cost of living crisis.

What they are saying about this blog and its author

- Normal Mouth

- Matt Withers, Wales on Sunday

- Eleanor Burnham AM

- The Cynical Dragon

- Inside Out

- The Cynical Dragon

- A Change of Personnel

- 'Willy Nilly' on Wales Home

- Rob Williams, the Independent

- July 2003

- August 2003

- September 2003

- October 2003

- November 2003

- December 2003

- January 2004

- February 2004

- March 2004

- April 2004

- May 2004

- June 2004

- July 2004

- August 2004

- September 2004

- October 2004

- November 2004

- December 2004

- January 2005

- February 2005

- March 2005

- April 2005

- May 2005

- June 2005

- July 2005

- August 2005

- September 2005

- October 2005

- November 2005

- December 2005

- January 2006

- February 2006

- March 2006

- April 2006

- May 2006

- June 2006

- July 2006

- August 2006

- September 2006

- October 2006

- November 2006

- December 2006

- January 2007

- February 2007

- March 2007

- April 2007

- May 2007

- June 2007

- July 2007

- August 2007

- September 2007

- October 2007

- November 2007

- December 2007

- January 2008

- February 2008

- March 2008

- April 2008

- May 2008

- June 2008

- July 2008

- August 2008

- September 2008

- October 2008

- November 2008

- December 2008

- January 2009

- February 2009

- March 2009

- April 2009

- May 2009

- June 2009

- July 2009

- August 2009

- September 2009

- October 2009

- November 2009

- December 2009

- January 2010

- February 2010

- March 2010

- April 2010

- May 2010

- June 2010

- July 2010

- August 2010

- September 2010

- October 2010

- November 2010

- December 2010

- January 2011

- February 2011

- March 2011

- April 2011

- May 2011

- June 2011

- July 2011

- August 2011

- September 2011

- October 2011

- November 2011

- December 2011

- January 2012

- February 2012

- March 2012

- April 2012

- May 2012

- June 2012

- July 2012

- August 2012

- September 2012

- October 2012

- November 2012

- December 2012

- January 2013

- February 2013

- March 2013

- April 2013

- May 2013

- June 2013

- July 2013

- August 2013

- September 2013

- October 2013

- November 2013

- December 2013

- January 2014

- February 2014

- March 2014

- April 2014

- May 2014

- June 2014

- July 2014

- August 2014

- September 2014

- October 2014

- November 2014

- December 2014

- January 2015

- February 2015

- March 2015

- April 2015

- May 2015

- June 2015

- July 2015

- August 2015

- September 2015

- October 2015

- November 2015

- December 2015

- January 2016

- February 2016

- March 2016

- April 2016

- May 2016

- June 2016

- July 2016

- August 2016

- September 2016

- October 2016

- November 2016

- December 2016

- January 2017

- February 2017

- March 2017

- April 2017

- May 2017

- June 2017

- July 2017

- August 2017

- September 2017

- October 2017

- November 2017

- December 2017

- January 2018

- February 2018

- March 2018

- April 2018

- May 2018

- June 2018

- July 2018

- August 2018

- September 2018

- October 2018

- November 2018

- December 2018

- January 2019

- February 2019

- March 2019

- April 2019

- May 2019

- June 2019

- July 2019

- August 2019

- September 2019

- October 2019

- November 2019

- December 2019

- January 2020

- February 2020

- March 2020

- April 2020

- May 2020

- June 2020

- July 2020

- August 2020

- September 2020

- October 2020

- November 2020

- December 2020

- January 2021

- February 2021

- March 2021

- April 2021

- May 2021

- June 2021

- July 2021

- August 2021

- September 2021

- October 2021

- November 2021

- December 2021

- January 2022

- February 2022

- March 2022

- April 2022

- May 2022

- June 2022

- July 2022

- August 2022

- September 2022

- October 2022

- November 2022

- December 2022

- January 2023

- February 2023

- March 2023

- April 2023

- May 2023

- June 2023

- July 2023

- August 2023

- September 2023

- October 2023

- November 2023

- December 2023

- January 2024

- February 2024

- March 2024

- April 2024

- May 2024

- June 2024

- July 2024

- August 2024

- September 2024

- October 2024

- November 2024

- December 2024

- January 2025

- February 2025

- March 2025

- April 2025

- May 2025

- June 2025

- July 2025

- August 2025

- September 2025

- October 2025

- November 2025

- December 2025

- January 2026

- February 2026

- My Photos

- The views on this website are personal and should not be assumed to reflect the policy of the Welsh Liberal Democrats or the Liberal Democrats. I do not accept any responsibility for the content of any websites linked from this blog nor should such be implied by my linking to them. Links exist to provide a wider experience of politics and life on the internet or to reciprocate for links here. The views of those commenting on posts are those of them alone. They are published to provoke debate and their publication should not be takem as an endorsement by me.

- Published and promoted by Peter Black, 115 Cecil Street, Manselton, Swansea, SA5 8QL on behalf of himself

- Hosted (printed) by Blogger.com (Google.inc) of 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043 who are not responsible for any of the contents of these posts.

The longest running blog by an elected Liberal Democrat politician

"The Liberal Democrat AM's site is fast-achieving cult status as surfers check out the latest musings on his personal web log."

Richard Hazlewood, South Wales Echo

"highly readable and, in part, quite entertaining....the website is certainly worth a visit"

Brian Walters, South Wales Evening Post

"a double espresso of dull. This is a man who has almost cornered the market in pedestrian prose and who unwittingly mimics the what-I-had-for-breakfast blog so beloved of the mainstream media."

"the Welsh political blogosphere’s Face of Boe"

"A political anorak"

The late Patrick Hannan on 'Called to Order'

"Refreshingly honest"

"Irresponsible"

"Proof that there's nothing geeky about being a blogger"

Ciaran Jenkins

"one of the more sane political representatives in Wales"

"a slightly sad bastard with a low attention threshold"

'Sometimes nutty as a Snickers bar but always entertaining'

'A barmy Lib Dem'

“Peter always says what he thinks. He’s well known for that."

Lord German

'The Assembly Anorak'

'a predilection for garish ties can come across as geeky, but is a decent communicator and all-round AM'

Western Mail

'an AM who is rather more useful than many give him credit for being'